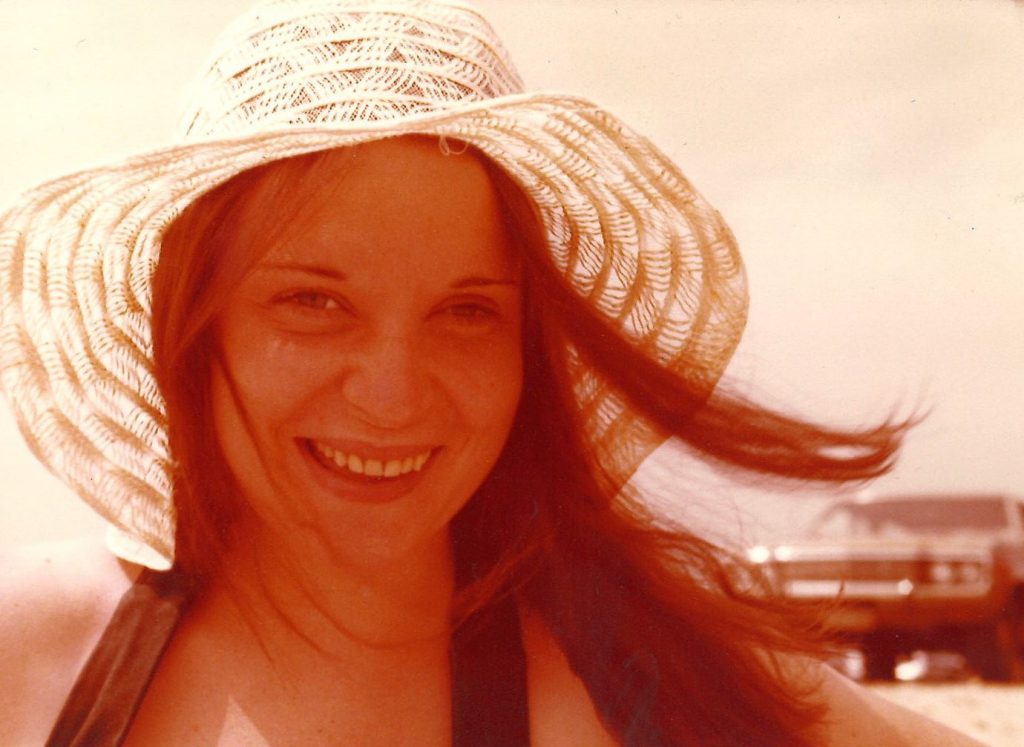

Jeanne Wiley (Becky’s Mom) in 1978, a few years after her cancer diagnosis

Ocular or uveal (meaning “of the eye”) melanoma is very different from cutaneous (“of the skin”) melanoma. Learn more about this rare form of melanoma.

When I was growing up, I noticed my mom, Jeanne, had a peculiar habit: if I was on her left side when we walked together, she would always move me over to her right. I can still remember the sensation of her stopping, gently grabbing my hand or my waist, and maneuvering us until I was on her right side, so she could see me.

When 3-D movies became popular in the 1990s, Mom didn’t have much interest in seeing them. Because she doesn’t have any depth perception, the blurry images that you see without 3-D glasses stay blurry for her even with the glasses on.

I vaguely knew that my mother had a “special eye” that she couldn’t see out of, but I didn’t really think much about it until I was in high school. That’s when she told me about her ocular melanoma.

I remember one of the first times we talked about it: I was sitting at the kitchen table while she made dinner. I said something about hating my pale legs and the taunts of “Casper” from my classmates and mentioned that I was thinking of going to a tanning salon. I burned — badly — when I was in the sun, but some of my friends went to tanning salons and they said I wouldn’t get hurt.

Mom stopped what she was doing and looked over at me. “Oh Becky, don’t do it,” she said. “My cancer may have been caused by a sunlamp.”

I don’t remember asking for details at the time, though her words made enough of an impact on me that I never went to a tanning salon. Over the years, my Mom and I occasionally talked about her cancer, especially when I started working at The Skin Cancer Foundation. Also known as uveal melanoma, ocular (meaning “of the eye”) melanoma is very different from cutaneous (“of the skin”) melanoma. It’s also rarer. With cases of ocular melanoma popping up in the news — including 50 people in North Carolina and Alabama — it felt like it was time to help my mom share her story.

First Signs of Trouble: Angles, Floaters and Flashes

Mom first noticed something was wrong with her eye on Christmas Day, 1975, when she was 22 years old. She had recently finished nursing school and had moved back home to her parents’ house in Beacon, New York. One of her brothers had received a pair of binoculars as a gift, and she was playing with them, focusing on the Christmas tree across the room. At one point she shut her right eye to create a telescope and realized she couldn’t see clearly out of her left eye — her vision was cut off on an angle.

A couple of days later, she visited an optometrist who checked her eyes and said she needed new glasses. “Even then I didn’t think, ‘It’s got to be more than that,’” says Mom. “I got the glasses, and within a week or two I started having more symptoms.”

First, she started experiencing floaters. “It was like little dots blocking my vision,” she remembers. “It would happen randomly. My vision would suddenly cut off in my left eye, so I got in the habit of closing that eye, and then I could see fine.”

She contacted an ophthalmologist and made an appointment for two months later. In the meantime, things got worse and she started seeing flashes of light, “like someone was taking a photo on my left side,” she says. “At first I would turn to look, but then I got used to that, too.”

Then she started having dizzy spells. During all of this, Mom continued working at a local hospital. One Friday while she was assisting a doctor with a procedure she began to feel faint. “I remember I said, ‘Doctor, I’m going to pass out,’ before I sort of slid down a wall.”

The doctor moved her to an empty bed and called the nursing supervisor. They started asking Mom questions about her health, and she told them about her symptoms and that she had an appointment with an ophthalmologist scheduled for the next month. So, they sent her home early to rest.

That evening at home, she received a phone call from the ophthalmologist; the nursing supervisor had contacted him. After my Mom described her symptoms, he told her to come to his office first thing Monday morning.

Getting a Diagnosis of Ocular Melanoma

My grandmother drove my mom to her appointment, where the ophthalmologist, Andrew Dahl, MD, looked carefully at Mom’s eyes. After the exam, he sent her back to his office and got my grandmother from the waiting room. Then he told my mother that she had a tumor in the back of her eye.

“Thank God my mother was with me. She had the presence of mind to ask the doctor if it was malignant. I was just too stunned. I immediately started to wonder if I was going to die.”

Dr. Dahl couldn’t tell Mom if the tumor was cancerous. For that she would need more tests, so he recommended she see a tumor specialist at the Harkness Eye Institute at Columbia Presbyterian (now known as Columbia University Medical Center, New York-Presbyterian Hospital) in New York City.

Within a week, Mom was admitted to the hospital for four days of tests and scans. One of the tests she remembers most vividly was called a radioactive phosphorous (P32) uptake test. She was injected with a radioactive dye and then monitored for 48 hours, while the dye traveled through her body. If cancer was present, the radioactive phosphorous would attach itself to the cancer cells. She was put under general anesthesia while doctors cut into a muscle alongside her eye and used a radiation detector to see if there was a higher “uptake” of the dye in the eye compared to surrounding tissue.

If my Mom had been diagnosed today, the testing to confirm ocular melanoma would be very different. Brian Marr, MD, who heads the Ophthalmic Oncology Service at the Harkness Eye Institute, says that advanced imaging technology has replaced the P32 uptake test. Today, doctors use clinical examination, optical coherence tomography (OCT) and high-resolution ultrasounds to scan the tumors and make a diagnosis.

Unlike with many other forms of cancers, a biopsy isn’t necessary to proceed with treatment. “In most cancer centers, if you don’t have a pathologic diagnosis, no one will treat the patient because there’s no proof it’s really cancer,” says Dr. Marr. “But because we’re so accurate in diagnosing ocular melanoma with visualization through some of the imaging that we have, it’s one of the only types of cancer we’re allowed to treat without pathology.”

As for my mom and her uptake test back in 1976: all the dye had traveled to her eye, which confirmed that the tumor was cancerous. Fortunately, the cancer hadn’t spread beyond the tumor, which was encapsulated by a thin layer of tissue. But the tumor was beginning to grow and touch the optic nerve, which is what caused the flashing lights and dizziness.

Looking to the Past for Clues

The doctors at the Harkness Institute asked Mom many questions about her past to find out how far back symptoms may have gone. Once she started thinking about it, Mom realized how many times she’d fainted as a teenager. She had lost consciousness several times after even just light hits on the head — once after being hit with a snowball. She had also passed out at three high school dances, each time when strobe lights were turned on. It’s possible that her tendency to faint was tied to the tumor pushing on her optic nerve.

The doctors deduced that she had always had a mole in the back of her eye, but some sort of trauma had likely triggered it to turn into a cancerous tumor. That’s when my mom remembered the sunlamp.

It was the 1960s, and she hated her pale legs then as much as I would in the 1990s. First, she tried lying out in the sun, on the roof of her parents’ house, for hours. Each time, she held out hope that the inevitable sunburn would turn into a tan. But it never did, so she bought a UV-emitting sunlamp from her local drugstore. She clipped the lamp to the desk in her bedroom and moved around so the light would hit her legs, arms, chest and face. She only used it two or three times and remembers burning herself badly enough that she decided it wasn’t worth it. Though she kept the lamp for years, she never used it again.

Unprotected sun exposure can seriously damage the eyes and surrounding skin, leading to vision loss and conditions from cataracts and macular degeneration to eye and eyelid cancers, but experts say there’s no known association with ultraviolet (UV) light and uveal (or ocular) melanoma. “If you look at the tumors genetically, skin melanoma versus uveal melanoma, the genes are significantly different,” explains Dr. Marr. “In skin melanoma we know that UV radiation causes certain genetic mutations, which are found in the tumors, but we don’t find those same types of mutations in the uveal tissue.”

Another factor to consider: Unlike your skin, your eyes can filter out UV light. Most ocular melanomas begin in the middle of the eye (in a layer called the uvea). Both the cornea and lens protect the uvea and the light-sensitive retina by blocking 99 percent of UV radiation.

Mom acknowledges that she’ll never be sure what caused her cancer. “But I often wonder if being that close to that lamp is what turned what would have been a benign mole in my eye into a melanoma.” Even without evidence, her story and speculations were enough to keep me from tanning beds.

Deciding on Treatment

On the last day of my mom’s hospital stay, the doctor who had administered the P32 uptake test confirmed the diagnosis of ocular melanoma. He told her that the treatment was relatively simple: She would need to have an enucleation — the removal of her left eye. If the cancer had spread, she would have needed more extensive surgery to remove muscles or bone surrounding the eye, as well as chemotherapy. Relatively speaking, she was lucky.

The doctor told Mom that the surgery could be done at the Institute, or she could have it done at the hospital in Beacon where she worked. She wanted to be near her friends and family, so she elected to have Dr. Dahl, her ophthalmologist back home, do the surgery for her.

Her surgery was scheduled for March 16, a week before what would have been her first appointment with Dr. Dahl if the nursing supervisor hadn’t stepped in.

Editor’s note: In 2022, the FDA approved tebentafusp-tebn (Kimmtrak®), the first immunotherapy treatment for adult patients with uveal melanoma that has spread to other parts of the body or can’t be removed with surgery. In 2023, the FDA approved a drug-device combo, melphalan hydrochloride for injection/hepatic delivery system (HepzatoTM KIT), for uveal melanoma patients who have some types of liver metastases. Visit our treatment glossary for more information.

Learning to See Again

As predicted, the surgery went well. Mom spent five days in the hospital, though these days enucleation is typically an outpatient procedure. She remembers a bit of dizziness for the first day or two, and headaches that went away within a week.

The hardest part was adjusting to monocular (single eye) vision. Mom had to retrain her right eye and brain to work together without the benefit of depth perception. For example, she remembers trying to paint her nails in the hospital and not being able to line up the nail polish brush with her nails. Something as simple as pouring a cup of water from a pitcher required practice. An occupational therapist at the hospital recommended she use a cup-and-ball toy to improve her hand-eye coordination, and she spent hours practicing.

“It was annoying, but everyone told me that my depth perception would get better,” Mom says. “In the grand scheme of things, it really wasn’t that bad.”

She was worried about driving, but my grandfather took her out to practice, just like when she was 16. “It took a little while to judge the distance to stop signs and stoplights, but eventually I got the hang of it. The only trouble I had was with parallel parking, but I was never any good at that anyway. To this day I just avoid it.”

At first Mom only had a piece of gauze over her eye, with a metal shield and a piece of tape. One of her aunts sewed her a selection of cloth patches and she wore them for a month before she was fitted for an artificial eye.

Life With an Artificial Eye

Mom describes the space where her eye used to be as “like the inside of your cheek.” She removes the prosthetic eye to clean it occasionally and treats the area with natural tears when it gets dry (typically from dust, air conditioning or dry heat). Every few years, usually when the prosthetic starts to get uncomfortable, she visits an ocularist — someone who specializes in creating and fitting artificial eyes — to have the eye refitted or replaced. Over the years, her lower lid has thickened, so the ocularist thins out the bottom of the prosthetic to make it fit better. She has also experienced some drooping of her top lid where the bone has receded. It’s possible that cosmetic surgery might help, but Mom is reluctant to have a procedure when there are no guarantees it will work. “These days the appearance of it annoys me,” Mom says. “But I know that I can’t worry about that every day.”

Over the years Mom has found ways to adapt. She knows where to sit in a restaurant booth or around a conference table, so she can see everyone. She learned to tell new coworkers about her eye, so they knew she wasn’t ignoring them if they happened to approach her from the left. “I have a constant bruise on my left forearm from walking into doorknobs,” she says, “but things could be so much worse.”

On March 17, 1978, almost exactly two years to the day after her surgery, she met my Dad. They were married a year later, on St. Patrick’s Day 1979. My brother, sister and I were born over the next six years.

Jeanne and her husband, Dick, on their wedding day

“At first I thought I was never going to get the chance to marry and have kids, which is all I wanted,” Mom told me. “But once I knew I could still have that life and continue my work as a nurse, I considered myself lucky.”

Over the years she’s taken tap classes, given zip-lining a try, and these days she’s busy chasing after my brother’s twin toddlers, her first grandchildren. “As bad as it was at the time, losing my eye to melanoma didn’t really impact my life in the long term,” Mom says. “I never let it stop me from doing everything I wanted to do.”

Jeanne with her grandkids

Maybe Mom’s experience never stopped her from doing everything she wanted to do, but sharing her story stopped me from making some of the same mistakes she had. For that, and a million other things, I’ll always be grateful to her.

Whoops! With Becky on her left, Jeanne turns her head to look at the bride.