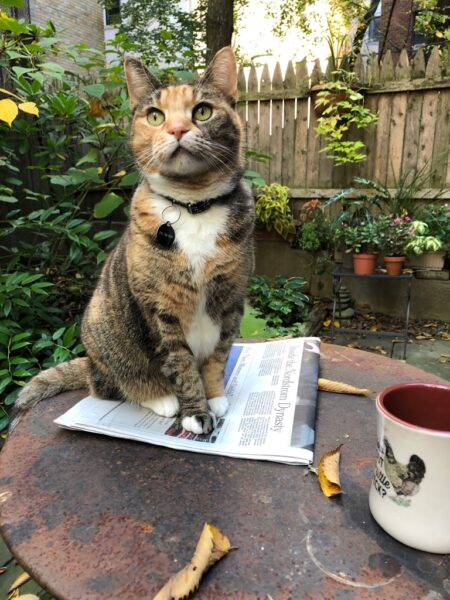

Polly, getting comfortable on day one in her New York City digs back in December 2018.

Our beloved pets can get sunburned and develop skin cancer, too. One writer reflects on losing her cat to the disease – and what she’s hoping others will learn from it.

By Barbara Peck

Grief is hard. You want it to stop, but you don’t know how to get closure. After losing my beloved cat, Polly, to skin cancer, tears well up with the slightest memory. I still see her out of the corner of my eye. And I wonder if I delayed her surgery too long.

Polly was a lucky cat to land with me back in November 2018. A friend was driving a country road in the Catskills of New York when he spotted a small tortoiseshell cat among the trees. Kindhearted George pulled over, opened the car door and she jumped right in! Clearly, she’d been someone’s pet, but now she was lost and needing a home.

Love at first sight: Barbara and Polly bonded immediately.

Since there was no cat rescue group in the area, George posted on Facebook about the cat, asking if anyone recognized her — or wanted her. No one claimed her. George and his wife had two kittens and felt they didn’t need another. I saw his photos and thought, “That could be my new cat!” I’d been catless for about a year, and something about this little creature spoke to me. George jumped at my offer and even offered to drive her to my place in New York City.

We bonded immediately. My vet estimated her age at 3 to 4 years and confirmed she was healthy. Lucky she was, having landed with a lifelong cat lover who even has a small, fenced backyard — in Manhattan! I didn’t let her outside till spring and kept my eye on her, but once given the privilege, she never once jumped the fence. “She’s a smart one,” I’d say. “She knows when she’s well off.”

Polly loved being a city kitty with a little bit of garden. But then, in late June 2022, I noticed a swelling on her neck. Polly’s vet performed a fine needle aspiration and reported “a lot of atypical cells.” He suspected a squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), one of the most common malignant skin tumors to affect cats. Could sun exposure have caused the SCC? I’ll never know what her Catskills life had been, but my backyard is surrounded by high-rises, so she got precious little sun there.

Surgical excision would be the most beneficial treatment, the vet told me, but first, they’d have to determine how far the tumor had spread and whether it was removable. Palliative options included a steroid shot or intralesional injection to reduce the mass, or pricey chemo or radiation therapy. He didn’t say treatment was urgent. We’d planned a family trip later in the month, so we went ahead with that (leaving my son Oliver home to care for Polly).

In August, she went back to the vet. An X-ray showed the mass hadn’t spread, but the ultrasound indicated a carotid artery was involved — one of two major blood vessels that send blood to the head. This wasn’t a dealbreaker; if we proceeded with surgery, Polly could survive with only one carotid artery. The veterinary hospital sent an estimate, and I consulted with my sons, who both felt that operating was the right decision. But I thought I would put it off just a bit, as the vet had said that if she was eating and drinking well and not in apparent pain, delaying treatment was OK. It’s easy to be in denial about an illness when the patient seems fine.

But the course of cancer can change quickly. One morning, we noticed the swelling on her neck had ruptured and fluid was seeping out. Polly wasn’t eating. My veterinarian’s office was closed, so I cabbed to an emergency pet clinic in Midtown. There, a vet cleaned up what was probably an infection and administered antibiotics and pain meds. I knew it was time to invest in surgery for my sweet girl.

On the morning of the surgery, the vet called with bad news. The tumor had metastasized and entered her throat. This development indicated that surgery would not be successful. The vet suggested it was time to say goodbye, and I knew I had to accept the inevitable. With sorrow in my heart, I held her, petted her and told her how much I loved her. I was surprised by how loudly she purred before I let the compassionate staff take over.

There’s nothing good about losing a beloved pet. Friends advise adopting another cat right away; others suggest taking time to grieve. I’m in the middle as I write this. Of course, I still miss her. I’ve learned from this experience that even young cats can get seriously ill — just like people. If telling Polly’s story encourages anyone to consult a vet when they sense something’s “off” in their pet’s habits or behavior — or to be more vigilant about checking their own skin — that would give me solace.

Polly loved her safe, fenced-in backyard in New York City, where she could smell the flowers, watch the birds and sit on the news, says Barbara.

Getting Treatment

Treatment options for dog and cat skin cancer are similar to those for people, says Jill Abraham, VMD, a veterinarian in New York City.

Usually surgery is required, although sometimes laser surgery is an option. Radiation may be a possibility for some skin cancers. And cryotherapy, laser surgery or topical treatments are options for precancerous spots (yes, pets get those, too).

And with advances in immunotherapy medications, there are veterinary oncologists saving the lives of beloved pets with advanced skin cancers, too.

See our (human) Treatment Glossary for more information.

Pet Prevention

The best way to prevent skin cancer is to protect your skin from the sun — and it’s the same for our furry friends. Here are some veterinarian-backed tips for keeping pets safe.

- Shade. The best protection for pets, veterinarians say, is to provide shade for them all year long, and get them out of the sun. Also, because animals don’t sweat the way people do, it’s harder for them to cool themselves. Don’t forget lots of water for outdoor pets. “And never leave a pet in a car unattended,” says Dr. Abraham.

- Clothing. For pets who have to be out in the sun, consider clothing. “More companies are making rash guards and sun protection clothing for dogs,” Dr. Abraham says. “There might be some that cats could fit into, if you can get them to tolerate it! Even UV-protective T-shirts that are made for people could be an option for some dogs. And I know of at least one company that makes sun-protective eyewear for dogs.”

- Window treatment. Remember that windows allow dangerous UV rays to penetrate, too, both at home and in your car, so you might consider getting sun protection film or shades for the windows.

- Sunscreen. Dina Rovere, VMD, a veterinarian at Happy Tails Veterinary Hospital in Shrewsbury, New Jersey, advises sunscreen for pets who are going to be outside a lot: “Say they’re going on a long hike on the beach and it’s high noon, absolutely. I tell people to put sunscreen on the nose and sun-exposed parts of the ears. Do what you can to protect them.” Dr. Abraham says, “It’s best to distract the animal while the product dries completely so it’s less likely that they’re going to ingest any of it.” She recommends a sunscreen that is made for dogs and cats. Pets don’t know not to eat the sunscreen!

Barbara Peck is an editor and writer living in New York City. While she wrote this, she was enjoying two new cats she adopted but still misses Polly dearly.